How many more citations do reviews (especially meta-analyses) receive compared to other types of articles?

Published:

Review studies (particularly systematic reviews and meta-analyses) are said to be very important in the scientific literature and they are often placed at the top of the hierarchy of evidence (which is debatable, but I think that most researchers and practitioners still usually see these reviews as more important than most primary studies).

However, I haven’t found much literature (especially in Psychology) that quantifies exactly how much greater the impact of reviews with or without meta-analysis is compared to other types of articles. The only study I’m aware of is this paper from the field of medicine by Patsopoulos et al. (2005) which, indeed, found that meta-analyses were cited more often than any other type of research.

So, taking citations as a proxy for impact (which is definitely not the most comprehensive way of capturing the real impact that research, e.g., real-world applications, but is the easiest way to measure impact) I tried to quantify this for Psychology and over a large period of time (last 20 years) using a rough search in Web of Science1.

As of 10 November 2024, I downloaded all items that WoS indexed as Psychology every two years from 2004 to 2024 (using the search string (SU=(Psychology)) AND DOP=(20XX-01-01/20XX-12-31) and exporting via InCites), excluding articles that WoS did not categorize as empirical articles or reviews (e.g., letters, editorials, etc.). To identify meta-analyses, I selected items that contained ‘meta-analy’ in the title. Articles were selected using the categorization made by WoS (which excludes reviews). Reviews were selected using the WoS categorization of reviews and those that contained ‘systematic-rev’ in the title (WoS misclassifies some reviews as articles even they contained ‘review’ in the title).

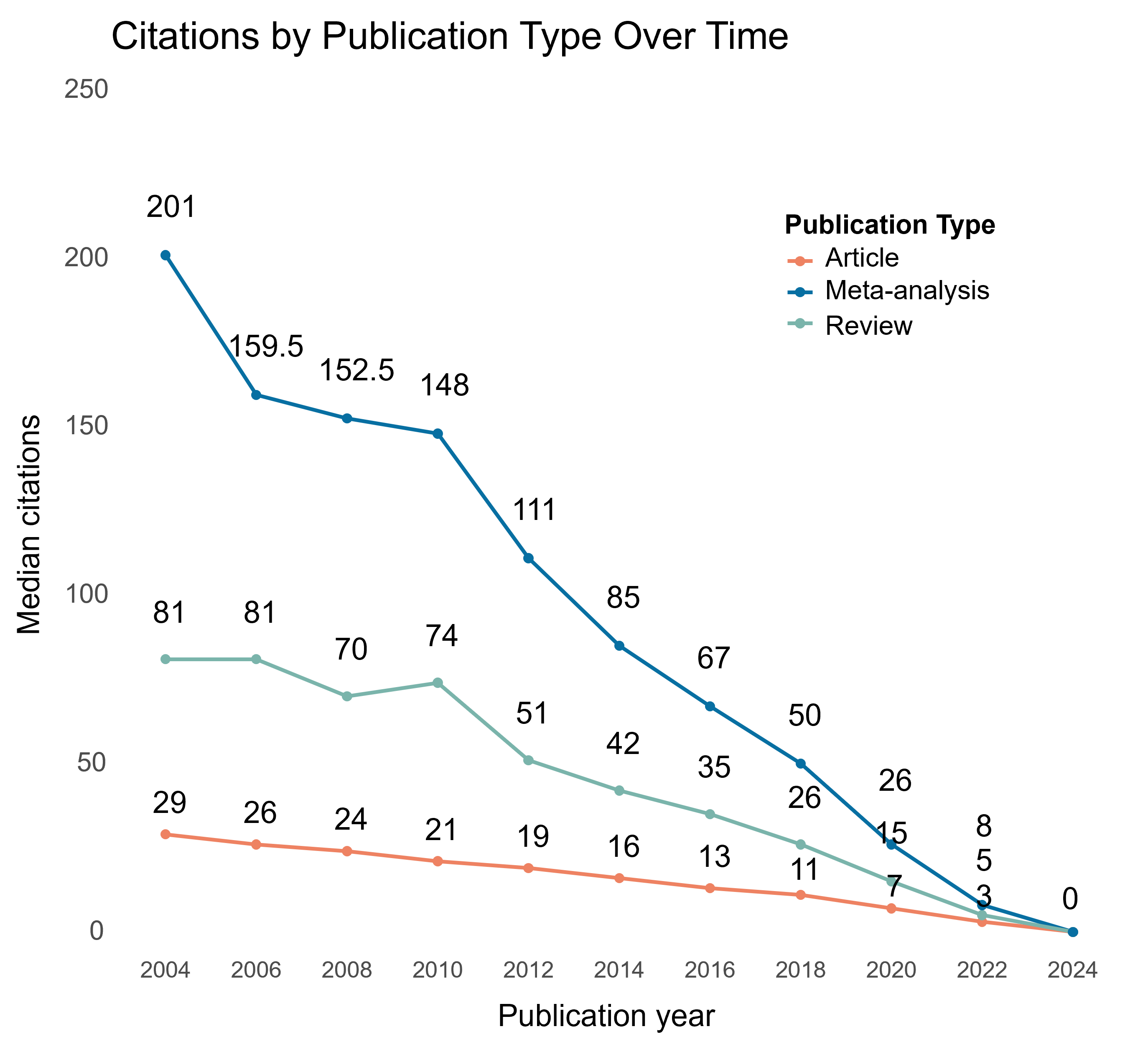

The plot below shows the median number of citations as of November 2024 that articles published from 2004 to 2024 had.

After 2-4 years, reviews and meta-analyses already became more cited article types and these differences increased over time, especially in the case of meta-analyses. In the case of reviews, they are cited about 3 times more than other article types. In the case of meta-analyses, it is about 5 times after 10 years and more than 6 times after 20 years2.

The data and code can be found here: https://osf.io/y8k3t/

References:

Patsopoulos, N. A., Analatos, A. A., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. JAMA, 293(19), 2362-2366.

Another approach to try to capture the impact that research can have in real life is to see if it is cited in policy documents. The most comprehensive database of policy documents is Overton (Altmetric also provides information on this, although I think its coverage is lower), but at the moment, I don’t have access to it. ↩

I repeated the analysis selecting systematic reviews only, selecting those items that had ‘systematic rev’ in the title. Systematic reviews appear to be slightly more cited than the items categorized as ‘review’ articles here (which includes non-systematic reviews) but because in the first years (2004 - 2008) it has only detected a few cases (e.g., 16 cases in 2004), this estimate may not be very accurate. ↩